Alexi Gladstone

What are the different components of intelligence? | Estimated Read Time: 7 mins

The Different Components of Intelligence

09/14/2024

It’s worth noting that most of this blog is not very scientific and is mostly just a useful abstraction for how to view the different components of intelligence (which is especially useful for thinking about current model capablities or benchmarking). The different aspects of intelligence are abstract ideas, don’t necesssarily represent the underlying way the mind works, and may not encompass all different portions of intelligence. If you come up with other aspects of intelligence please email me :)

1) Memorization and Knowledge

Memorization broadly refers to the ability to recite information. Knowledge goes a step beyond this, and involves applying memorized information to new contexts. Knowledge often involves understanding at a deeper level than sole memorization.

As of 2024, Large Language Models (LLMs) are pretty good at memorization and, are half decent at knowledge, but fail at most of the other aspects of intelligence discussed below.

2) Learning Efficiency

Because of evolution, it’s easy to see that most modern animals (and even plants), learn pretty efficiently.

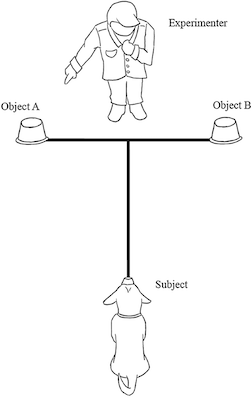

As an example of animal learning efficiency, if you put a treat on the floor under a cup, and then put down another cup (with the dog watching), and then point to the cup without a treat under it (see example image, link), dogs may follow your point. However, often after 1 or a few times doing this dogs will often learn not to trust your point. This example demonstrates that dogs will learn quickly given just a few or even 1 example/’shot’/trial.

Within the context of AI, the idea of learning efficiency has long been a focus. People often claim that modern models are great at zero-shot or few-shot learning… but is this really the case?

I believe that “Zero-shot” learning (and few-shot similarly) can be interpreted in two distinct ways:

-

Not seeing something at all during training and being able to predict it on the test set: E.g. if you were doing supervised classification, not seeing a dog at all during training, but knowing what a dog is during testing. This is a harder problem and, in my opinion, is impossible.

-

Not specifically training or learning for a downstream task but still being able to do the task: This is relatively easier and has been solved in some cases, such as CLIP for image recognition or LLMs being able to extract entities. These models were not trained for the specific task, yet are still able to perform it. It’s worth noting though, that these models have seen the concepts/tasks they are being tested on throughout pre-training (or some form of pre-training).

The first definition is the literal definition of zero-shot, while the latter definition is the more commonly used and easier version.

So How Does Pre-Training Data Affect “Zero-Shot” Performance?

The paper “Do Multimodal Models Really Achieve Zero-Shot Generalization?” states the following:

“We consistently find that, far from exhibiting “zero-shot” generalization, multimodal models require exponentially more data to achieve linear improvements in downstream “zero-shot” performance, following a sample inefficient log-linear scaling trend.”

This finding aligns with the second definition of “zero-shot”, and supports the idea that with modern AI we are still far from true zero or few shot generalization/learning efficiency (the first definition).

Recent benchmarks, such as ARC-AGI, further support this. ARC-AGI measures the abilities of models to learn a completely new task, given just a few examples and then perform that task. Humans can achieve nearly 100% on this benchmark, but modern LLMs only score around 21%, and top approaches score less than 50% (both of these values are based off of when this blog was written in 2024). It’s worth noting that problems in the benchmark get progressively (one could even say exponentially) more difficult, so the jump from 21% to 50% is very significantly easier than the jump from 50% to 100%.

If you are now tempted to say, "What about LLMs which are great at few shot learning?"

LLMs are not good at few shot learning unless they have already been trained on data similar to whatever task is being performed. For benchmarks such as ARC, which are completely out of distribution for the pre-training data of LLMs, they do terrible at few shot learning. AI researchers have become accustomed to calling models good at few shot learning, even though models have often seen similar examples during pre-training hundreds or even thousands of times during training (https://arxiv.org/pdf/2404.04125).3) Generalization, Creativity, and Invention

Generalization, in the context of intelligence, can broadly be defined as “the ability to apply learned knowledge or skills to new and varied situations.” Similarly, creativity can be thought of as “the ability to generate novel and original ideas or solutions by combining existing knowledge or skills in innovative ways1.” It’s easy to see that the further someone is able to generalize, the better their creativity will likely be. It’s also worth noting that creativity and generalization are spectrums, and not binary skills that intelligent systems either do or don’t have.

One cool thing about creativity, is that great creativity can lead to invention.

Now, if we were to look at our society now, and compare it to societies from 1,000 years ago, 10,000 years, etc; the differences we’d see could be explained by one thing–invention. Inventions, one after another, have led to the revolutionization of our society. Without invention, humans would be no different than apes.

The Most Challenging Aspect of Intelligence

I’ve ordered this blog based off of which aspects of intelligence I believe to be easiest (memorization, knowledge) to hardest (generalization). Although I don’t think I can argue for this ‘ordering of intelligence attributes’ scientifically, a simple evolutionary argument can be made. Animals, and even plants as we have seen, are capable of memorization and few shot learning. However, their abilities to invent with the same success as humans is limited. As such, we can say that humans have better generalization/creativity than other animals and plants, and that this is something extremely challenging to develop through intelligence (since only humans have it).

Compression

Tons of AI researchers love mentioning how compression is linked/core to intelligence (paper, twitter mention). I’ve always agreed with this statement. To me, however, it was never clear why (at least with an elegant explanation). I think the framework discussed in this blog to look at different aspects of intelligence provides a great lens, here’s how:

Compression in an of itself is an aspect of memorization/knowledge. Let’s say animal A has compressed 1000 bits of information into 100 bits, and animal B compressed the same information into 10 bits. Both animals have memorized the same information.

However, the difference in these memorizations, is that in the future, animal B will likely be able to generalize to more situations. Why, you ask? Intuitively, animal B has likely memorized more of the core reasoning/explanation than animal A, and that will likely explain future situations better. Mathematically, there are also some cool proofs for this (Ilya talk, related paper).

Therefore, we can see that further compression of the same information leads to better generalization. As discussed, I believe generalization is likely the most challenging aspect of intelligence, and hence compression is likely core to high levels of intelligence.

Perhaps the saying “simplicity is key” hits a bit harder after learning this :)

Generalization of Modern Models

While some recent papers have stated that LLMs can come up with novel ideas and do research at the level of humans (paper1, paper2), there are numerous problems with the methodology of these papers (that I don’t have the time to write about). If these papers really did work well, then people doing frontier research would be using LLM generated ideas, rather than what people are doing now which is having real humans do research. LLMs, being trained to predict the next token over existing text corpuses online, are nowhere near being capable of generating their own creative ideas that will eventually lead to technological invention. (I’m not claiming here that LLMs can’t assist in the idea generation process, as I agree they are helpful with that. Rather, I’m claiming they are nowhere near being able to generate their own, good ideas.)

Summary

AI in 2024 (mostly dominated by LLMs) is capable of memorization and knowledge to a wide extent. However, modern models fall short of being able to learn efficiently (few-shot), and are nowhere near being able to generalize to the same extent as humans. As most plants and animals are capable of sample efficient learning, I have no doubt that eventually we will have AI that learns as efficiently as plants and animals. To me, the quadrillion dollar problem is–how do humans generalize so well (so much better than even close ancestors such as apes)? And how will we ever train models to be able to generalize to the same extent as humans, such that they can come up with really great ideas that revolutionize society. I have a blog about this very topic!

Footnotes

-

One may be tempted to say that creativity need not be defined by composing observations/existing knowledge (i.e. that we can generate entirely new ideas). First, modern research points to the fact that humans are likely generating new ideas based off of combinations of past experiences/observations. Second, as an informal experiment, try thinking of something completely new that is not composed of previous things you have seen/heard/etc. If you manage to succeed at this task (which I would be very surprised about), ask ChatGPT to see if it is truly novel or can be decomposed. If that isn’t convincing, email me, and I’ll try and convince you that you are wrong :). ↩